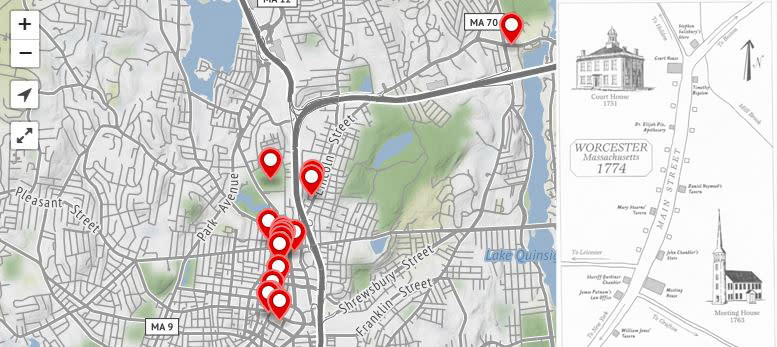

The stops on this tour relate to Worcester in the Revolution, a heady time for this young town and, indeed, for all colonists. We hope you will enjoy this revolutionary tour of Worcester, courtesy of the Worcester’s Revolution: A Town that Defied an Empire project by the Worcester Historical Museum in collaboration with Digital Worcester and students at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

At the time of the American Revolution, Worcester was a rural, agricultural community established some sixty years earlier. The population of about 1,900 was roughly one-tenth that of Boston. Everyone, including professional gentlemen, farmed. Settlement clustered along what is now Main Street from Court House Hill to the Common where the steeple of Old South Meetinghouse dominated the skyline, and along the road to Boston (Lincoln Street). Small grist and sawmills hugged the banks of waterways amidst widely scattered farms. Some stately two-story dwellings graced the landscape, but most people lived in modest one-story houses of two or three rooms. Broad swaths of trees provided ample firewood and building stock. Dirt roadways were rutted by the hooves of livestock and cart wheels. Cattle grazed on the Common.

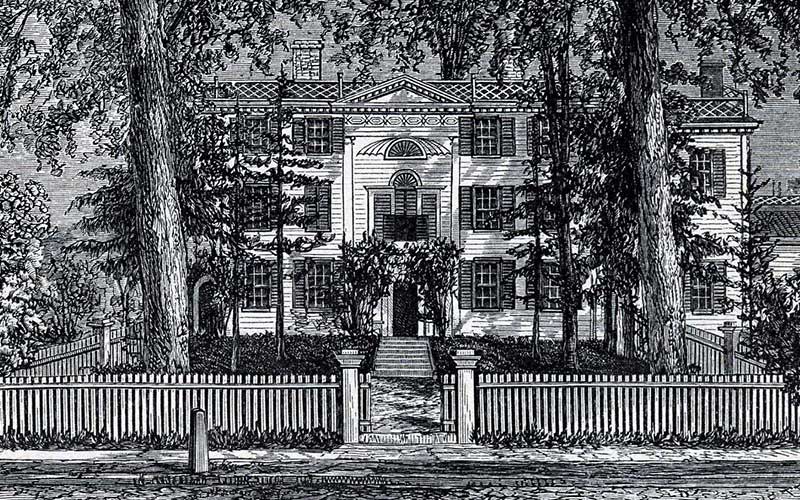

Salisbury Mansion

40 Highland Street

In an unprecedented display of grassroots activism, Worcester County citizens gathered on the grounds of Salisbury Mansion in 1774 to march over and close the court house in protest of the recently passed Coercive Acts. To read more, see Ray Raphael, The First American Revolution (2002). The mansion at that time stood at what is now Lincoln Square (the site of the former Boys’ Club); it was moved up the hill to its present location in 1929.

Hancock House

formerly south corner of Grove and Lexington Streets

After fleeing Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, John Hancock came to this house to await the arrival of his document-filled trunk (left at the Buckman Tavern) and his compatriots before traveling to Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress. This house originally stood on the road to Boston, just south of the Oaks (DAR). The next owner, Governor Levi Lincoln Sr. (1749-1820), served in President Thomas Jefferson’s cabinet and as attorney general of the United States. It was moved to Grove Street by a new owner in 1846. When it was torn down in 1910, the front door of this fine 1741 mansion was placed in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution.

Rural Cemetery

180 Grove Street

Isaiah Thomas’s remains, located in the front right corner, were moved from Mechanic Street Burial Ground to Rural Cemetery in 1878. Among the more than 13,000 buried there today, you will find additional Revolutionary-era names as members of numerous local families were reburied there after the cemetery opened in 1838, among them Stephen Salisbury I.

Second County Court House

2 Main Street

Outraged citizens closed this court house in 1774 in “the first American Revolution.” It was built in 1750, replacing the original court house, and was subsequently replaced several times by ever-larger structures. The site is now occupied by the former Worcester County Court House at Lincoln Square. The second county court house was relocated and today is a private residence at 6 Massachusetts Avenue.

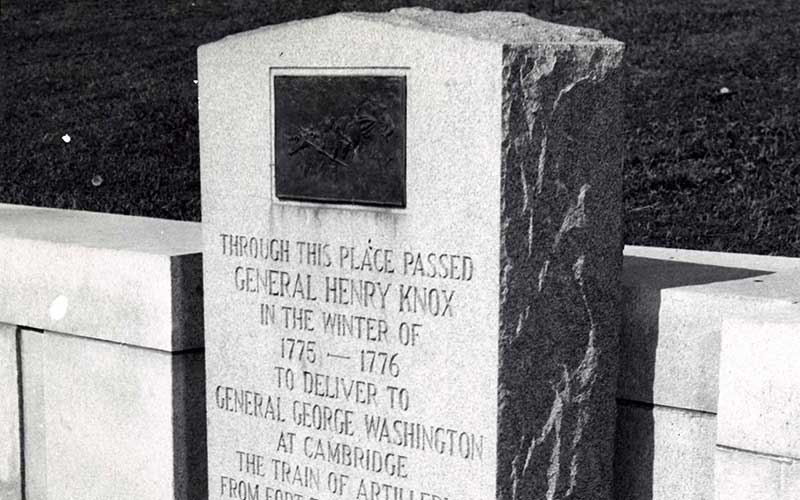

Knox Marker

corner Highland and Main Streets

In May 1775, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold captured the British outpost at Fort Ticonderoga, New York. Later that year George Washington sent Henry Knox to bring the nearly 60 cannons from the fort to Boston where they were deployed at Dorchester Heights. Their presence helped force the British to evacuate the city in March 1776. The Knox “train of artillery” passed through many Massachusetts towns, including Worcester. In 1927, a monument was placed at the corner of Highland and Main streets, in front of the former Worcester County Court House.

Isaiah Thomas House

former vicinity of 2 Main Street

Under threat of physical harm, Patriot printer Isaiah Thomas (1749-1831) fled Boston in 1775 to set up his press in Worcester. His newspaper, the Massachusetts Spy, was the first to report on the fighting in Lexington and Concord. His house, built on upper Main Street, was moved after his death to the rear of the court house lot to make room for construction of a new court house in 1845. The house was torn down in 1923. Fireplace tiles saved from the wreckage are on exhibit in the museum’s Rice Gallery.

Isaiah Thomas 2nd location and site today.

Heywood Tavern

corner of Elm and Main Streets

When Patriots occupied the court house to protest the Coercive Acts on September 6, 1774—setting in motion the first American Revolution—Royal officials (judges, justices of the peace, attorneys, and the county sheriff) fled to safety at Daniel Heywood’s Tavern until the events of the day could be resolved. It was later replaced by Bay State House.

Heywood Tavern as it looked in the 1830s and site today.

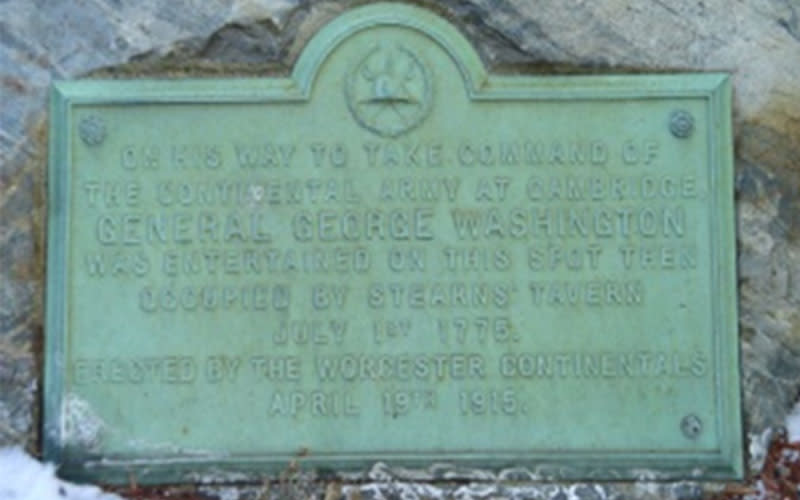

King's Arm Tavern

corner Elm and Main Streets

In 1774—the year of the first American Revolution—the tavern was under the proprietorship of Widow Mary Sternes. Tories met here to draft and sign their 1774 protest. A plaque located at the base of Elm Street notes its Patriot significance: “On his way to take command of the Continental Army at Cambridge George Washington was entertained at this spot then occupied by the Stearns [sic] Tavern, July 1st 1775.”

Declaration of Independence

455 Main Street

The star in front of City Hall marks the spot where, on July 14, 1776, Isaiah Thomas stood on the western porch of Old South Meetinghouse and delivered the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence in Massachusetts. The plan was to read it at Boston but, fearing interception by British patrols occupying the city, it was decided it would be read in Worcester by the distinguished patriot. The marker was placed by the Worcester Society of Antiquity (now Worcester Historical Museum) in 1897.

Old South church and site today.

Timothy Bigelow Monument

Worcester Common

At the convening of the Provincial Congress in October 1774, Worcester representative Timothy Bigelow (1738-1790) proclaimed—at the behest of his constituents—that unless the Massachusetts Charter of 1691 was immediately restored, “you are to consider the people of this province absolved … from the obligation therein contained” and thus free to rise from the ashes and form a new government. With these words, the people of Worcester effectively declared independence from England two years before the official Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. In 1861, descendants erected a monument in his honor.

Timothey Bigelow Monument on the Worcester Common.

Gardiner Chandler Mansion

478 Main Street

Sheriff Gardiner Chandler (1723-1782) was a prominent Tory, active in royalist resistance until threatened with confiscation of his considerable property. (His unrelenting brother John was banished, never to return, and his property seized.) Gardiner built a fine Georgian mansion in 1750 on Nobility Hill, across the street from Old South. When the house was torn down in 1867, a built-in cupboard (“beaufat”) was salvaged and is now installed in the museum’s Rice Gallery.